The Secret Maps: Production Diary Shooting Starts

Shooting starts next week and I’m drafting a post to wrap up how pre-production has concluded. However, in the meantime, I came across a posting on the Dish that appealed to me because it combined the subjects of my last film and my current film by addressing how women, who provide the majority of end-of-life care, are particularly impacted:

The burden of unpaid care work that women continue to shoulder plays a major role in women’s persistent economic inequality. Directly, there is the opportunity cost that comes when women cut back hours or drop out of the paid labor force to provide care; economist Nancy Folbre has referred to this cost as the “care penalty.” Indirectly, unpaid care work affects women’s compensation in the paid labor market. Research has shown that a portion of the gender pay gap is attributable to the fact that women with children are, on average, paid less than their otherwise identical counterparts. Another study found that working in a caregiving occupation is associated with a 5 to 10 percent wage penalty, even when skill levels, education, industry, and other observable factors are controlled for.

But…

As writer Jane Glenn Haas pointed out, eldercare isn’t sexy enough to be a feminist issue. It lacks the naughty allure of reproductive rights, the seductive appeal of body image. It doesn’t even have a sassy Lean In-like catchphrase. But it should be a feminist issue, since the numbers show that women are most likely to shoulder the responsibility of looking after parents in their twilight years, and the most likely to live well into those twilight years. A lot of them have missed out on career and educational opportunities. A lot of them—like my mother and her friends—are doing this by the skin of their teeth, with scant to nonexistent resources. A lot of them will outlive their spouses (if they have them), exhaust their pensions (if they have them), and die alone.

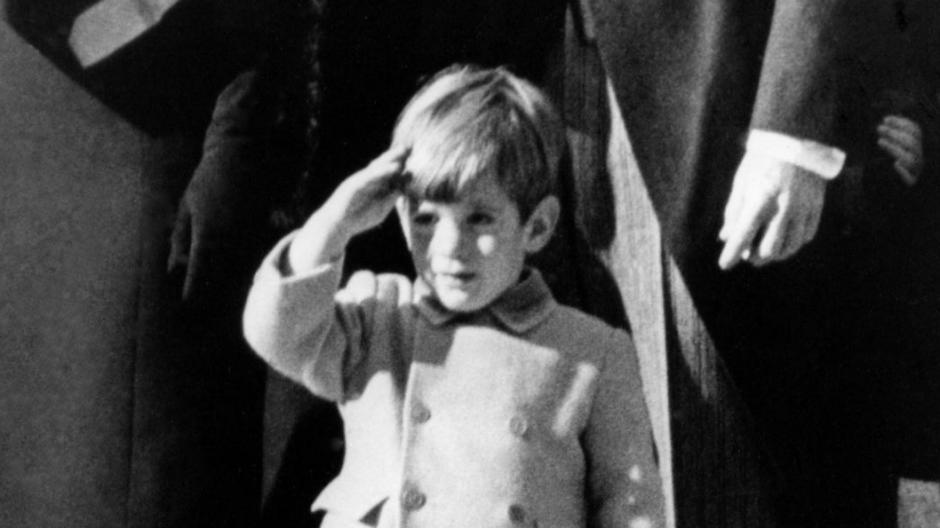

The fuller article on the Baffler is here. The blog post that started it all, a personal essay really, called Eldercare: The Forgotten Feminist Issue and quoted above is here. And I include the lovely picture of the mother of the writer, Jamie Nesbitt Golden, as this post’s featured image because all of us caregivers can relate.